---->JENELLE: This post may veer a little from the topics we usually engage with in our course, but I've been thinking a lot about the Solange visual album Anna presented last class, and the use of landscape, especially in "Stay Flo." I'm really interested in the way deserts are represented in art and especially cinema and especially music videos. Deserts often seem to signify dystopian aesthetics in cinema, and so in some way may have something to say about Afrofuturism, or they seem to be used as blank spaces ready for projected significance. They are just visually interesting spaces, and especially great for photography with all the weird reflected light (and I have definitely shot a lot in deserts myself!)—but they are also not blank spaces in that they have been historically (and often currently still) inhabited and have their own histories. I'm just thinking about landscape used as style, and if filmmakers have a responsibility to place, especially when they have no obvious connection to that place or no obvious recognition of indigenous relationships to that place. This feels really different than the use of place in films like Daughters of the Dust or Compensation, and I wonder if there is something somewhat settler-minded about using especially deserts this way (I am thinking about the history of the west and California, where white settlers acted like the desert was empty and ready for their projects/irrigation/speculation). Don't get me wrong—I also always love looking at the desert, and I don't mean for this to come across as overly critical of Solange! The representation of the desert just happens to be a pet interest. I'm also interested in thinking about how this might be a different conversation for white and Black artists (or others from non-white settler backgrounds)—is it different if your ancestry was or was not involved in extractive and genocidal settler imperialism in these spaces?

---->ANNA: This is really interesting! I see your point regarding the use of place as backdrop rather than place as imbued with history and culture (as well as intrinsic value). I can't quite make any complex argument as I'm not well-read regarding how we use the American desert in art, but I wonder if there's something more going on in the piece. I think there is a sense of communion with the space present, one that doesn't seem to claim the desert as Blank Space but recognizes a connection with it and sees it as populated rather than empty. The use of Afrofuturism vis a vis the desert backdrop definitely seems in line with a dystopian aesthetic trend, but I'm not sure if that is the only valence at work. There's something to be made of many of the desert shots being particularly of the West Texas desert. More than anything I'd say Solange is making a piece about what it means to be a Black Texan, and the desert is part of that conversation. The desert is home, a valence of home, a way of expressing Texas-to-Solange or Texas-to-Blackness more so than I think it is an ode to indigeneity or a disavowal of indigeneity. I don't think there's nothing to be said regarding indigeneity in this context, but I wonder if settler theory is not the right avenue for thinking about this, as it's primarily a mechanism of construing Black space.

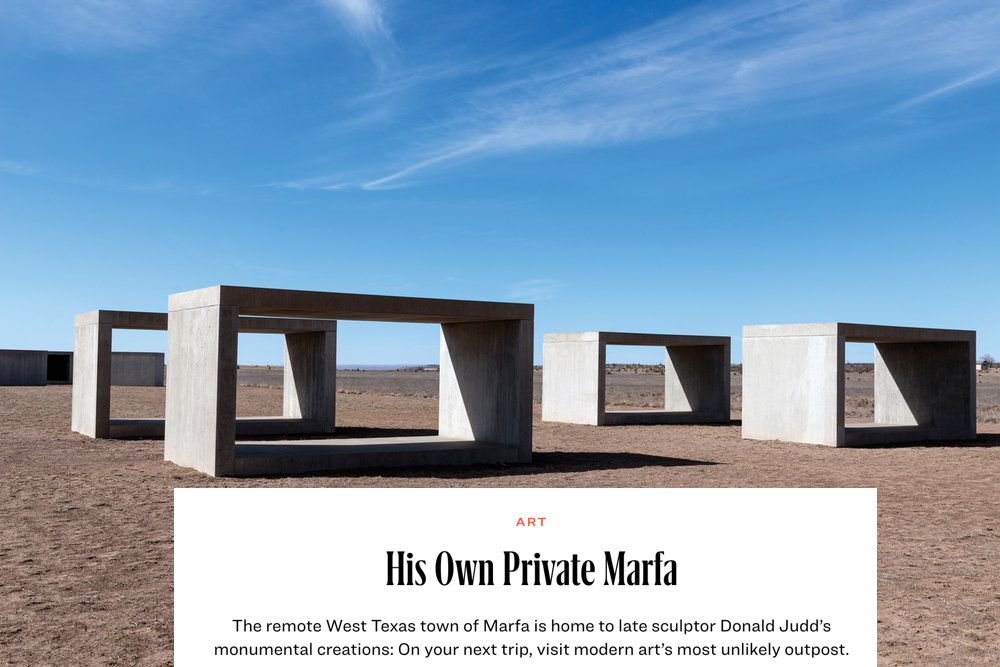

---->JENELLE: I'm interested in what you wrote about the West Texan deserts—I have to admit for me, this area feels very conceptually and geographically distant from the Houston area, in a way that makes it harder for me to read this as a piece expressing Solange's own Texan/Black Texan identity, but that's probably my own narrow-mindedness under the influence of the complicated legacy of Donald Judd in Marfa (and similarily, Georgia O'Keeffe in northern New Mexico).

Which makes me think about how my own references and assumptions are probably too influenced by the history of how white artists have conceptualized place. Which then makes me think about one thing this video does is represent Blackness in western spaces that have largely erased Black history—exactly to your point. I am also thinking about how Jane Campion (damned as she is for her recent comment about the Williams sisters) wrote, in defense of making an American western (and, well, queer) film as a New Zealand (and, well, woman) director: "The West is a mythic space and there's a lot of room on the range."

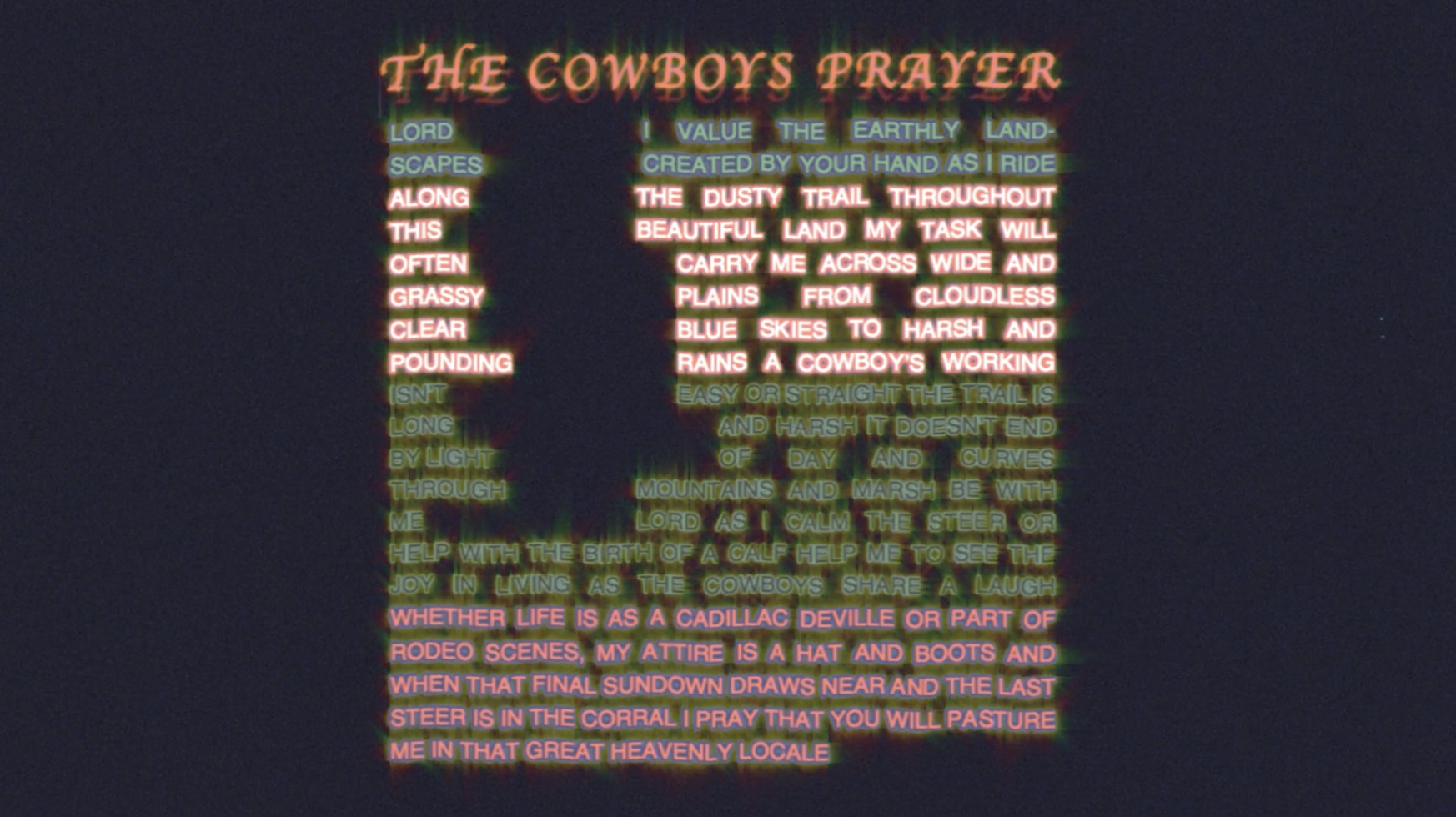

---->ANNA: A really fascinating scene in the film is a Black rodeo depicted in Texas (one of the prominent uses of the Texan desert) around 18:19 here as well as a complementary scene following it of these Black cowboys riding through the streets of Houston itself. I think this points toward what you're talking about regarding the Black western and how this film interrogates what it's trying to say about the desert itself as well as the commodification/liberation of the Western and the erased Black history with the American West. The cowboy's prayer, itself, seems a direct attempt to consider the film's use of the desert as something that is not merely aesthetic but critical to its meaning

The cowboy mantra is imbued with respect and valuation of the earth: "LORD I VALUE THE EARTHLY LANDSCAPES CREATED BY YOUR HAND AS I RIDE." The cowboy ethos, driven by love of beauty and love of the land, extends into the entire ethos of Solange's work. The Black Western is driven not by control and mastery of the land, but by deference to the creation of beauty, life, and landscape.

Not to mention this image is directly followed by the animated horse and cowboy of the imagined futurist colosseum! Very interesting to put together, especially in consideration of how much of the desert and the cowboy is actually a link to Solange's Texas and how much is it a link to the American conception of Texas as a place of conquering...

---->JENELLE: And thank you again for sharing Sojourner. I'm in Morocco this week and I've been thinking about how white-written science fiction has drawn so much from Northern Africa (Star Wars, Dune/contrast this to how the Tuareg are referenced in Black Panther)...

Then watching Sojourner this morning it just dawned on me that one thing I hadn't really been considering yet—which now seems very obvious—is that the desert in African American cinema can be a way to point to Saharan/Subsaharan Africa, connecting to both history/displacement (and maybe both the violence of that history as well as a time before that violence) and a speculative? restorative? future/possibility.

Tell me if I'm really turning too sharply toward my personal interests, but I'm wondering if you could help me with the philosophical language: I am thinking about how a place (let's say the West Texas desert) is, pre-sign/signification, and then how it is also densely signified: as a living site for itself, as a site of many histories (some violent, some erased), and as a site of metaphorical meaning (The West, the African continent, the Future, etc.). Maybe my anxiety about how landscapes are utilized in media draws on some fear that all these meanings & mythologies can prioritize human instrumentalization of the earth (materially and abstractly), overwhelm it with a sense of knowledge and mastery. Can we have an opaque relationship to place/the earth? How do Afrofuturist works (as well as Indigenous Futurisms, other non-"Western" futurisms) think of this relationship?

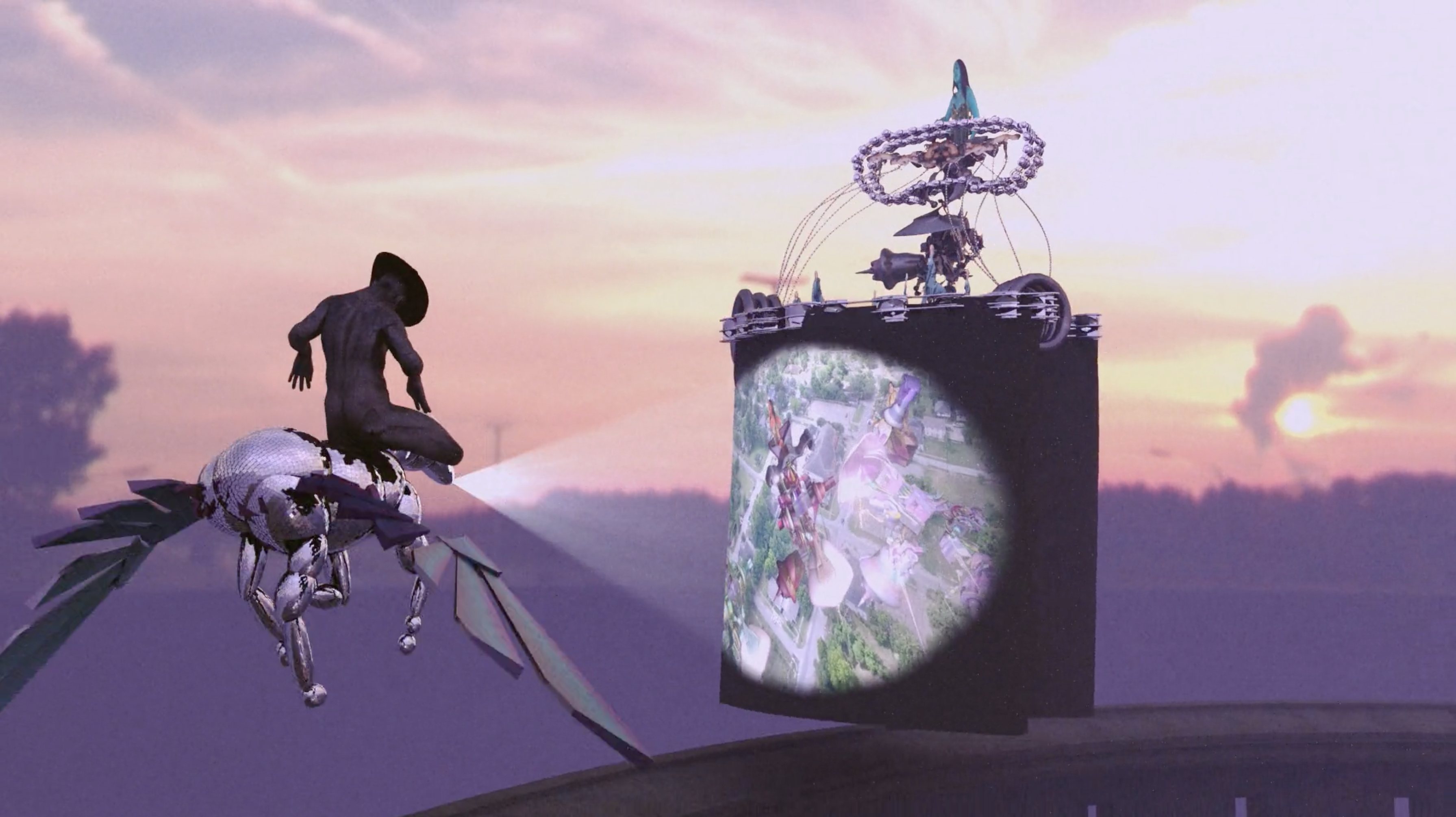

---->ANNA:Perhaps the difficulty here is in supposing that human symbiosis with the Earth has to be a form of instrumentalization or mastery, as opposed to communion or spirit. The prioritization of the human side of human-earth interaction is definitely the motivating factor for many if not most science fiction dramas, especially white ones, but it feels like a secondary concern to either of these works, both interested in mending, reshaping, and playing with how we create and live in our spaces. The world is all that is the case, the sum total of reality is the world.

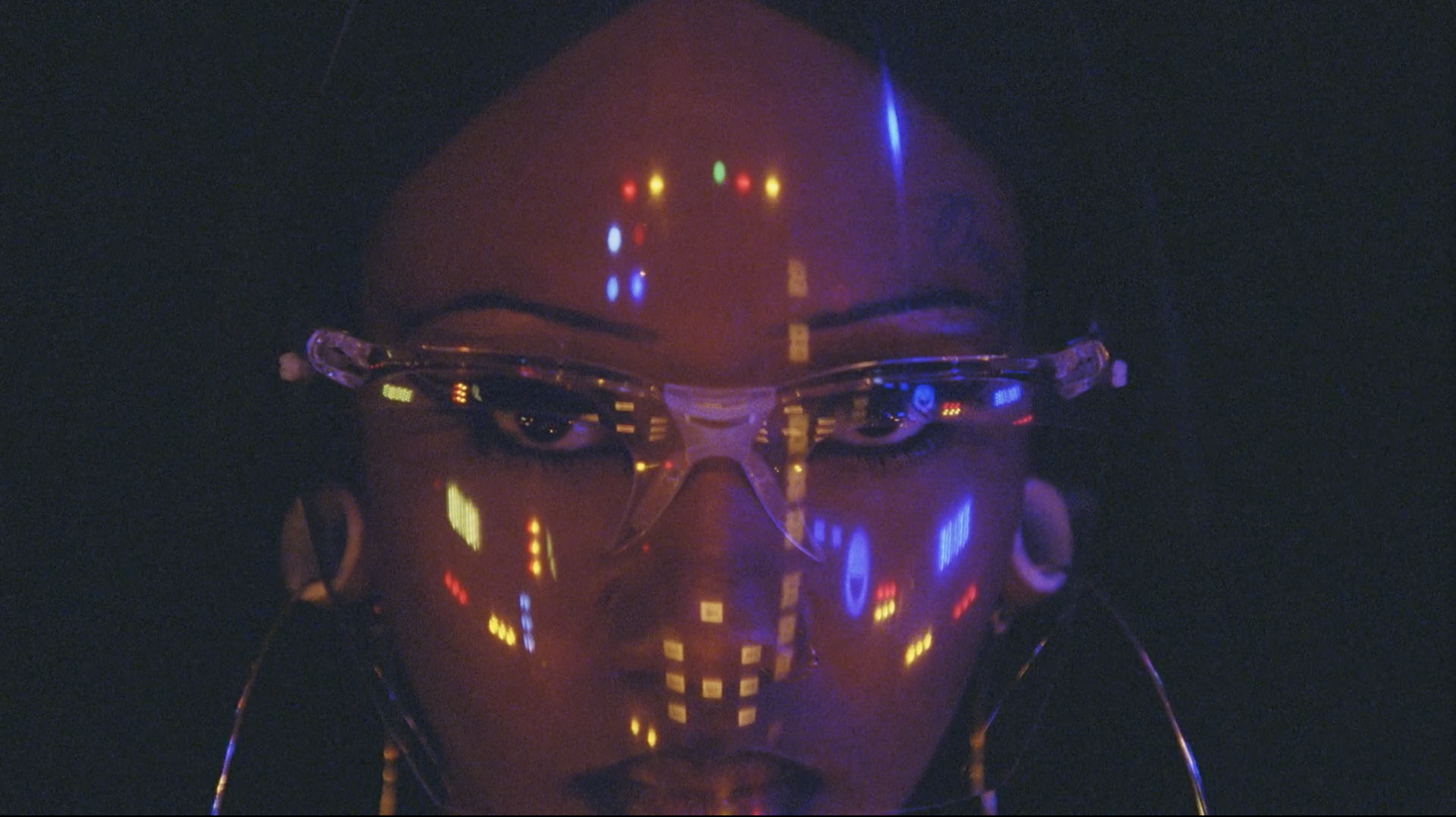

The predominant world view, operated by greater institution, is that the world is either apart from us or at our beckoning. I’m thinking here of reciprocity and of tending to the land as an integral action of care, of seeking to fill space [not, of course, in the white colonial perspective of land control] as an inherently animal function. The work that appeals to me in Afrofuturism, and the work I see in both Sojourner and in When I Get Home, is that it does not seem to shy away from filling space but rather thinks of our relationship to place as something to work toward. The argument may not be how can we avoid taking over the earth as much as how are we trying to get back to it? Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass opens up with an “offering” to weave “science, spirit, and story–old stories and new ones that can be medicine for our broken relationship with earth, a pharmacopoeia of healing stories that allow us to imagine a different relationship, in which people and land are good medicine for each other” (emphasis mine). The science-fiction slant of When I Get Home prioritizes the space ship, the neon lights and visors, the gaze of forward at the viewer. Sojourner holds our gaze in a similar way in its final shot,

is that an invitation to seek new ways of being [the Future] or is it an acknowledgment of the difficulties [white society] has created to stay on Earth? The directness of the gaze cues me to think both pieces are asking us to consider how we conceptualize future, Afrofuturism, and what comes next when it comes to thinking about the spaces and ways we inhabit.

---->continue dialog in the next space

---->return to first space