Glitching originates from the Yiddish “gletshn,” meaning “slide, glide [or] slip." The glitch is the slip away from the norm, both the error itself and action of erring. I glitch, I see a glitch. A glitch causing someone to lose hours of progress on their work is frustrating—a problem. On the other hand, a glitch in a video game allowing the player to phase through digi-walls, normally impassible barriers, gives them a leg up in completing a task or vanquishing an enemy. It is exciting to watch normative barriers fall, exciting to witness a world operating with new logics. The openness of glitching, the temptation of skipping through, of entering the world differently, of experiencing askew. The glitch body is a phenomenological form of the glitch, a way of moving closer to the digital disembodiment of the Online as well as a new manner of experiencing embodied presence in an increasingly digital world.

The glitch body foregrounds the anomaly, occupying a space pivoted against societally normalized identities. It pushes against the assumption of correctness—of the right way of operating—while also affirming its own situational location as Outside the norm. It is both the opposite to norms and outside the binary of this and that. It coopts the binary, makes it “blurry,” a threat to normativity. It “[claims] the right to complexity, to range, within and beyond the proverbial margins.” Some people are born glitching, a result of a socially bugged code, while others adopt the glitch as a means of living. We are cyborged by the material reality of our world, impossibly defined by the natural and the constructed entangled.

When I Get Home’s animated section on “Sound of Rain” creates a futurist, queer imaginary playground out of Houston’s Third Ward, incorporating rodeos, cowboys, and dance into its hyper-sensual, visually frenetic space. “Exit Scott (interlude)” plays over footage of a cowboy in the night, trotting along empty city streets. He’s wearing a strange futuristic helmet or visor. Rotating historical footage of cowboys and their horses are superimposed upon it, the screen flattening the decades between the Then and Now. The cyborged cowboy’s technology gives the impression that he is projecting this for us, seeing or feeling something for which we have no clear access.

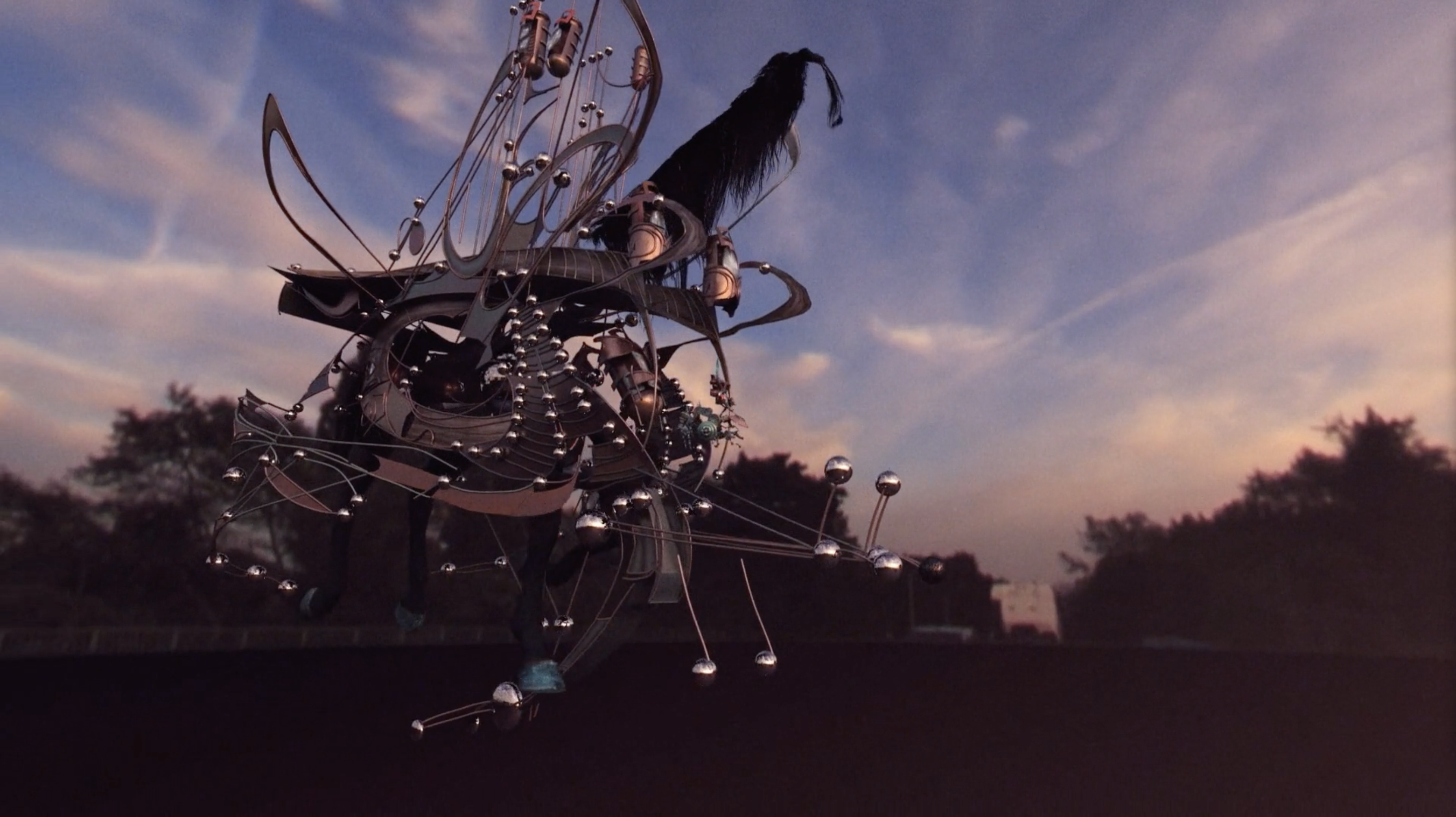

This atemporal space is punctured by a cut away from the Houston set-piece and into an animated amalgam of metals, gears, and hooves. The black steed from the last shot is now a Frankensteined horse, galloping against a pink and purple sky. Below the floating horse is a colosseum, a rodeo of senses. Crowds of caged figures, vaguely recognizable people, are as rendered two-dimensional paper people stuck in an endlessly looping dance. The repetition of the space creates a sense of continuance, the code keeps looping, but each time, the pattern seems to devolve further. The figures catch on fire, dissolve into a swarm of particles in humanoid shape, grow vines across their faces. Glitch takes root, glitch forms the foundation of the space.

Glitching gives space for “resisting the body as a coercive social and cultural architecture.” Acknowledging and prioritizing the glitch helps the work of deconstructing the body as a project of historical and present-day colonialism, ridding the body of the vestiges of “sex, gender, [and] geography.” By presenting us as viewers and consumers of culture with the undeniably fallibility of the body-as-material-binary-container, glitch gives space for new representations of the body, new ways of experiencing physically, emotionally, erotically, and radically. The glitch in When I Get Home is representative of the space-beyond-the-body, not aiming to free oneself of their physicality but instead represent physical space as a mutable and alive creature that does not inhabit the binary put on it by colonialist hegemony.

Thinking about digital [un]embodiment against the film’s ethos regarding the primacy of the natural in the rest of the film exposes a productive tension in the film. If the film, and the album at large, are concerned with the importance of spaces and finding home in physical place, where does this animated section, distorting and dizzying, fit? Resting on the film’s Afrofuturist leanings, the animation extends its interest into Houston as a space of speculation. Again, we reference the opening refrain of the album—“Saw things I imagined / I saw things I imagined.” Rather than showing a progressive, futurist space outside of Houston, we are re-rooted in Houston itself, especially in the Third Ward. Projected on top of footage of the Third Ward, the animation reflects a future of Houston as we know it and how Knowles wishes to see it. The neo-zydeco sound on top of the neo-cowboys, naked and dancing against the strange background, is a queered, erotic space. It projects the future of Houston which Knowles is consistently working to imagine—one where the Black body is given primacy both aesthetically and culturally. The body is glitched out of the realm of recognition, freed and joyful. Presenting the viewer with an onslaught of visual information, the scene essentially works to do the opposite—to clarify and pare down to the feeling, emancipated from the burden of accurate representation of reality.

How does one do the work of imagining things—peoples and spaces—and how is imaginative work theoretical, radical, and productive? The digital space is clearly an infinite expansion of the material space—anything that can be coded can thus be visualized and made ‘real’ in some dimensions of our understandings of ‘reality’—but how are even digital imaginings tempered by how we “read or render (in)visible” gendered and racialized bodies? The “Sound of Rain” section is preceded by a video collage of Knowles dancing in her bedroom, seemingly recorded on a webcam. Her identity is mediated through the digital even before it is digitized.

All of us are cyborged by the world, by our mediating the world.

---->turn back around

---->credits & sources